When we arrived in Burma we expected to see heavily armed soldiers patrolling the streets. Instead we were greeted by an army of stamp-toting bureaucrats. Our guesthouse had to report our whereabouts to three different authorities, seven times a day. This adds up to 21 forms to be checked, stamped and archived. Every day. Somewhere in Rangoon or Naypyidaw there must be hordes of skilled stampers and an ocean of overflowing file cabinets. Forms, licenses, and permissions are ever-present features of Burmese everyday life. To us, the totalitarian powers of the state, and the intricate web of complicity which all Burmese citizens by necessity are entangled in, is manifested in the stamp.

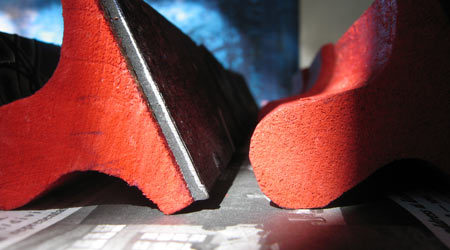

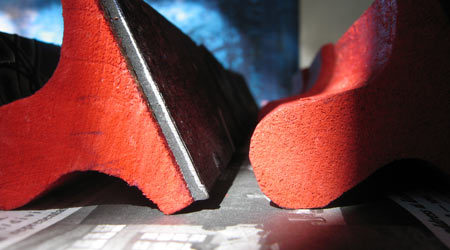

A painter we worked with showed us a series of pencil drawings in a plastic folder labelled ‘6-7 am’. We made a copy of one of his drawings, cut the paper into twelve pieces, all of the same size, and then convinced one of Rangoon’s many stamp makers to craft a rubber stamp for every piece of paper.

When exhibited, the twelve different stamps and a blue ink pad lie scattered on a small table. A set of white papers, empty except for a one-hour time interval such as ‘10-11 am’ or ‘1-2 pm’ written in the lower right corner, is attached to an adjacent wall. Exhibition-goers are invited to stamp the paper as they like. They can try to recreate the original drawing, choose not to do anything, or improvise a new motif using the stamps. Each hour one stamped paper is removed from the installation and fixed to a nearby wall, adding to a series of completed stamp-artworks.

The lone signature painter is the dominant model for artistic creation in Burma. By involving several co-creators (painter, interaction designer, stamp maker, stamper) in an unfinished process with many possible endings Timestamps complicates the role of authorship and, consequently, responsibility. An unfinished, participatory artwork is more elusive to the censors but is also more difficult for the initiating artist to make a living out of.

A few hours before the opening of a public exhibition in Burma a group of censors arrives. They inspect the artworks and sometimes ask the artist to explain their piece: What is this person in the painting doing? Why do you use red colour here? A work with only the slightest trace of nudity, violence or political imagery is promptly removed. Ambiguity is dangerous and discouraged. Each blurry face is potentially a secret portrait of the The Lady.

We were surprised that artists are given an opportunity, however arbitrarily interpreted and acted upon, to explain themselves or, in other words, to contextualise and describe their artwork in a way appropriate for the authorities.

We were also intrigued by the intimacy of these meetings between the artist and the censor. When standing in front of a deep purple-tinged painting of a naked woman in foetal position, the artist was asked by the censor: What did you feel when painting this? She replied that she hadn’t cried in public since she was six years old. She cries only through her paintings.

The Timestamps installation is partly conceived as a prop in a similar, but so far only imagined, meeting with the censor:

censor: What is this? What does it mean?

artist: It’s an installation where people can participate by stamping on that white paper on the wall.

censor: So, hmm, people could stamp anything they want?

artist: Yes, as long as they use these stamps. Of course you could always stay here and make sure the finished stamp-paintings are appropriate. I’m sure you are quite skilled at stamping.

The absurdity and naivety of this dialogue is matched only by reality. Most likely the form of the work is too unfamiliar for the censors even to engage in a dialogue. As one urmese artist bluntly predicted: They would not participate.

Stamps at the ready

Stamping participant in Rangoon

Signed by time